I was recently asked to talk on the topic of how African Art influenced Modern Art. I began by explaining what is meant by ‘African Art’. In this context it is considered to be a range of sculpture, mostly wood, from parts of West and Central Africa, including modern-day Congo and Angola. The talk was followed by another, describing pieces from a large collection from Congo, some of which are shown below.

Wooden objects were not made to last, but for a particular purpose and could be replaced, so there was no incentive to preserve them and there is little or no legacy of old pieces. The climate of this region and numerous insects which eat wood, also contribute to the lack of old pieces. The legacy of artistic history of this area is confined to more durable materials; for example, Nok terracotta statues, found in central and north-western Nigeria, associated with burial sites, but little is known of them or the civilisation that made them around the 1st century. During the 12-15th centuries in southern Nigeria, the Ife civilisation made terracotta images and from the 13th the nearby Benin kingdom made remarkable bronze heads and illustrated panels. An artistic history which continued after contact with Portuguese traders using brass objects melted down. The Portuguese also commissioned ivory carvings at coastal settlements from Sierra Leone to Cameroon, where they found existing skills. Some of these survive, as ivory is much more durable than wood, and give clear evidence that skilled crafts people were living in these areas. In Sierra Leone, carved stone figures, known as nomoli, are also found in fields. Their origin is unknown but they pre-date European contact.

The Dutch and English followed the Portuguese in trading along the coast, bringing trade beads (from Italy) and other goods to exchange for gold and ivory. As European exploration opened up the continent more traders and missionaries arrived. The missionaries were against what they saw as idolatry, so rounded up many wooden images and either burnt them gave them to ethnographic collectors. These collections were taken back to Europe; to private collections or to be displayed in the World Exhibitions which were popular from the mid 19th century in European capitals and American cities. Often ‘native villages’ were recreated, complete with ‘wild people’ for the entertainment of visitors.

After such exhibitions some of the buildings were retained and filled with the remaining exhibits, thus becoming museums. The Trocadero in Paris was one such example. It was museums of this kind that members of the public could subsequently see African curiosities. The relevance of such collections becomes clear when we consider that Paris was the centre of the European avant-garde art world at the turn of the 19th to 20th centuries, where artists such as Picasso, Matisse, Weber, Gaugin, and others socialised, worked together and visited each others studios.

African wooden sculptures were made for a variety of social, political and religious reasons by master craftsmen, trained during years of apprenticeship. Little is known of individual artists as there is scanty documentation. They were acknowledged locally by being praised in poetry and song accompanying the image, but these were mostly unrecorded and not passed on to collectors from outside the group. The images may have been made to illustrate desired social norms, commemorate life cycle events, to protect and heal, divination or to define power and leadership. They were often used as prompts for story telling and passing on knowledge, particularly during initiation ceremonies.

Images were hewn from wood, so constrained to some extent by the nature of the wood, its shape, its texture and density. The purpose of the image would also determine choice of wood; items to be carried by nomadic people would be made of light wood (eg. Dinka head rests), statues for outdoors would be made of mahogany for durability (eg. South Sudan death figures).

Images were not lifelike representations of individuals but abstracts of human form emphasising features of significance (head, eyes, hands, reproductive organs) which were not in natural proportions. The abstraction was to emphasise the essence of the image, the life force, and to represent ideals of beauty. For example smooth, black, well oiled skin was the sign of a healthy individual and many statues were oiled to blacken and smooth them to demonstrate this. Many female figures show elaborate hair arrangements and scarifications of skin which were also prized.

Horrific looking images were not made to embody evil, but to evoke a reaction from the viewer – to scare away evil spirits and unknown beings – to protect the owners. Often items such as metal nails were added by the empowerer of the image to release its power; to take on the essential elements of the added item – hardness of metal, animal qualities of horn.

Abstraction was not something known in European art before the late 19th century. Up to this time artists had been largely studio bound, painting still lives, portraits or landscapes from sketches. They aimed at a realistic portrayal of what they saw, or a romanticised version of mythological or religious stories. From the mid-19th century the Impressionists moved their easels outside and painted what they saw, capturing the changing light, the changing seasons, often in multiple versions of a scene.

The post Impressionists, like Van Gogh, took this further, expressing more emotion and spirituality in their works. They used more vivid colours and more stylistic composition. Paul Gauguin worked with Van Gogh and then became fascinated by ‘primitive’ (non-European) art, living in the South Pacific for some years and adopting bright colours and introducing a spiritual element to his work. He was a strong influence on young Pablo Picasso.

Rousseau was a self-taught ‘naïve’ artist who used unnatural colours, one-point perspective and painted imaginary landscapes. His works were laughed at until receiving some acclaim and exhibited in New York by Max Weber. Weber was also the first to send Picasso’s work to New York at a time when he worked with Alfred Stieglitz, an early promoter of modern art. Weber was an accomplished artist in his own right and he was in Paris in the early 20th century working and hanging out with Picasso and his crowd, including Gertrude and Leo Stein. Weber was the first American artist to be honoured with a retrospective of his work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1930.

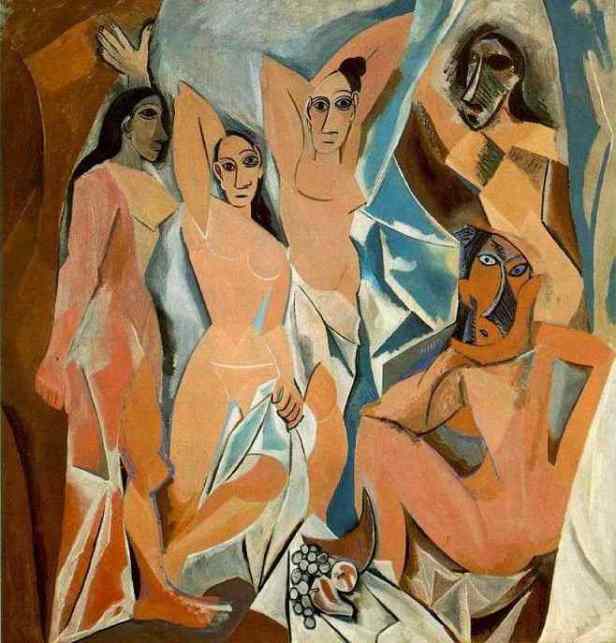

It was, of course, Picasso who was at the forefront of the avant-garde set and he who painted the ground breaking ‘Les Desmoiselles’, which shocked his friends when he first painted it in 1907. It wasn’t exhibited until 1916 and then, not again, until 1937. However it was seen by many artists, including Georges Braque, with whom Picasso worked to develop cubism. The painting breaks conventional perspective and composition. The subject matter is confronting and shows multiple viewpoints. Two of the women have distinctive faces which look remarkably like African masks.

Picasso denied knowing anything about African art, but this has been shown to be untrue. In the spring of 1907 he accompanied Derain to the Trocadero and returned to study the ‘primitive’ sculptures he found in the dark, dank rooms. Matisse and the Steins both collected African Art and Picasso himself began to collect, so his denial seems somewhat hollow. ‘Les Desmoiselles’ has subsequently been taken to represent many things: Europe’s descent into violence, the rise of women’s emancipation, relativity as per Einstein, and sexual frankness heralding Freudian theories. What Picasso himself intended is hard to know, but he did say later that ‘modernism is an art that wears a mask’. Learn more about the painting here.

The aim of cubism is to deconstruct an object, to get at its essence. These artists recognised this in African Art and began valuing these statues and masks as art rather than mere curiosities. They appreciated the aesthetic qualities expressed in the abstracted forms.

Cubism in turn influenced other genres: Die Brücke group in Germany – who had ethnographic museums in Dresden and Berlin for inspiration. The Italian Futurists were linked to Paris by Modigliani and Severini although their main interest was to depict movement in their works. There was also strong influence on the Art Deco movement with its clean lines, and simple design which contrasts with the floral, flowing Art Nouveau of the turn of the century.

The first major show of modern art in USA was the 1913 Armory show, held in the armoury of national guard in New York, Chicago and Boston, which shocked the public and had a profound influence on American artists. Further exhibitions followed some including African (or ‘Negro’) sculptures. In 1923 the Brooklyn Museum held the first exhibition which promoted African sculptures as ‘Art’.

US collectors began to include African sculptures in their collections and these influenced US artists. Alain Locke was the first African-American Rhodes Scholar in 1907 and he studied in Oxford and Berlin. He acquired a large Belgian collection of African Art (from Congo) which he encouraged African-American artists to study. He was part of the Harlem Renaissance movement.

African Art also had direct influence on sculptors of the time; Jacob Epstein (US/UK) is known to have owned a Fang sculpture, the influence of which can clearly be seen in Epstein’s work. Looking at the works of Brancusi, Modigliani and others, the abstraction of African art is clear. These artists in turn had an impact on Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and future generations of sculptors.

Despite Picasso’s lame denials, it is clear that African sculptures did have a clear influence on modern art. It opened the eyes of European and US artists to abstraction and the search for the essence of the subject. Max Weber said, “Art has a higher purpose than mere imitation of nature….A work may be ever so anatomically incorrect or ‘distorted’ and still be endowed with the miraculous and indescribable elements of beauty that thrill the discerning spectator.”

references:

http://www.theartstory.org/artist-weber-max.htm

http://www.theartstory.org/artist-picasso-pablo.htm

http://www.theartstory.org/artist-gauguin-paul.htm

http://www.theartstory.org/artist-rousseau-henri.htm

Armory show photo: https://www.newcriterion.com/issues/2012/12/the-armory-show-at-100

Other photos: authors own and of a private collection of Congolese art